Further Analysis into 8 different kinds of Laksa in Asia

YOUTUBE INSPIRATIONS

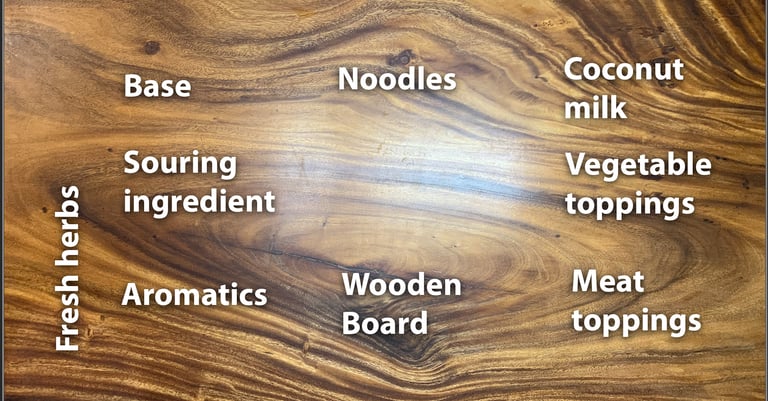

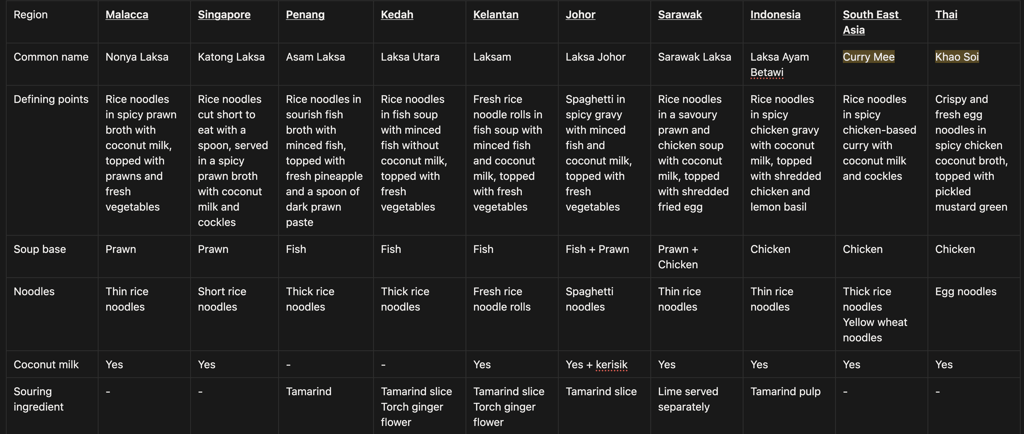

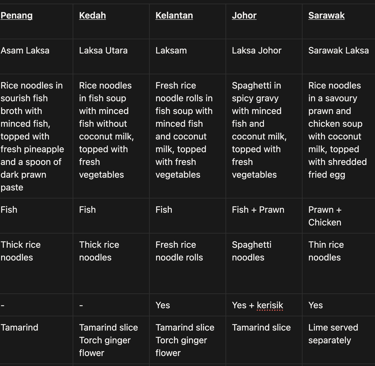

Laksa is actually one of the popular dishes that I didn’t really understand before I made this video. Is curry and laksa the same thing? Their ingredients look so similar. And there’s so many different kinds of laksa out there. By cooking each of them, I gained a better understanding of the soul of laksa. Essentially, we can analyse it from these attributes

Base: chicken, fish, or prawns

Noodles: thin noodles, standard ‘laksa’ noodles, or freshly made noodles

Souring agent: asam jawa or asam keping

Coconut milk: either yes or no

Rempah: generally the standard sambal aromatics of chilli, onions, garlic, lemongrass etc.

Fresh herbs: ‘laksa’ leaf, basil leaf

Vegetable toppings: includes fresh herbs and more, like bean sprouts, tofu puffs, cucumber, onion, chilli etc.

Meat toppings: chicken, prawns, cockles or clams

Here's how I arranged the ingredients generally on the table.

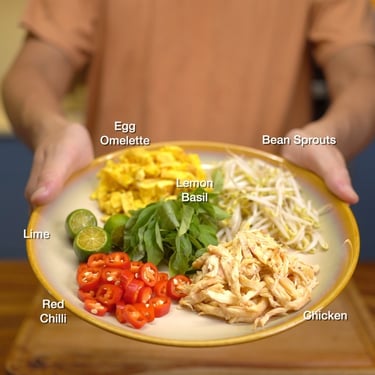

This is a matrix table of laksa ingredients to see how ingredients are transformed to the final dish. It also lets us analyse across the different types of laksa on the ingredients, base components, and toppings. (Note: I forgot to take a pic for Katong laksa, hence I reused Nonya laksa one. It's about the same, except that there should be fishcake...)

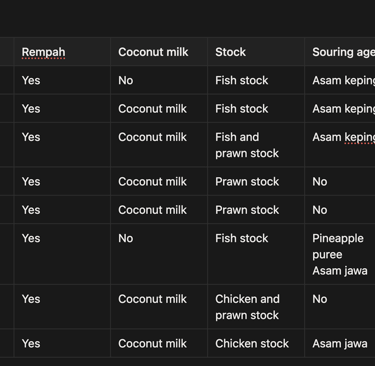

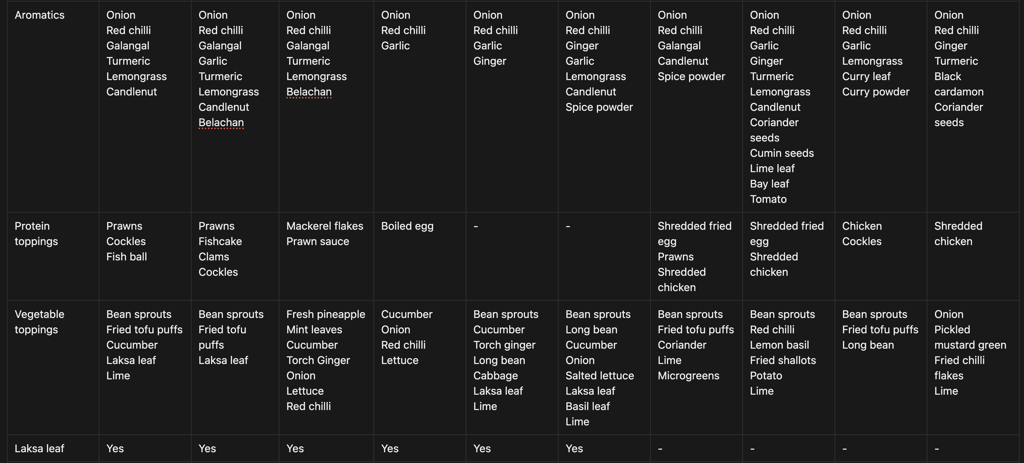

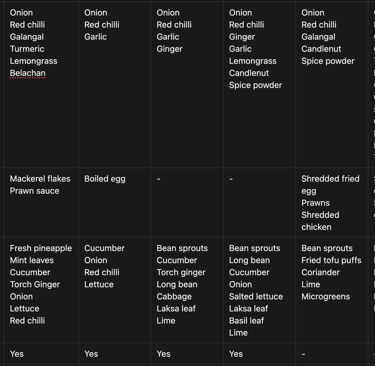

Here are some tables for further analysis across the different types of laksa. It’s interesting to see how Northern laksa tends to be healthier by the use of fish, and not frying the rempah in oil, whereas the Southern states emphasise on caramelising the sambal in oil, using prawns and chicken, and adding a generous amount of coconut milk.

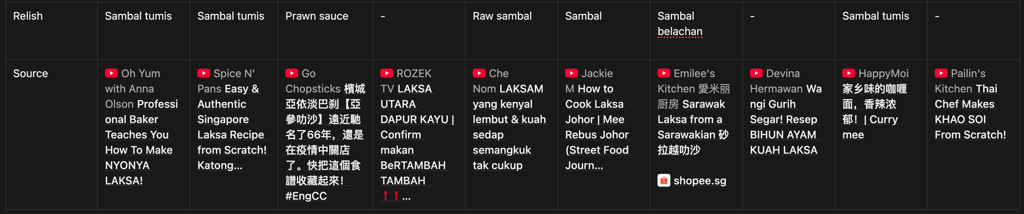

Here are the recipes in words which I used for reference to compare their ingredients. Generally the reference recipes are based on YouTube videos of the most prominent chefs or content creators to represent their region.

For the most original Nonya laksa, I have to mention Chef Wan who is probably Malaysia’s most famous chef and he’s also a Peranakan. In his book, his Nonya laksa recipe is based on his grandmother so it’s probably as legit as it goes for what Nonya laksa is like a long time ago. I really didn’t expect the soup base to include fresh prawn to come as texture. It seems like a waste to pound or blend fresh prawn meat, but it actually adds a luxurious touch to the base as I got to chew on bits of overcooked prawn bits. We’ll also see this in the Johor laksa.

For Katong laksa, Spice and Pans is the probably the most Singaporean cooking channel where Chef Roland takes us through a classic Nonya style recipe, emphasising on frying the prawn heads and pressing them to extract maximum flavour.

For Penang asam laksa, I featured a Malaysian lady speaking cantonese for a more authentic experience. She presents her ingredients really well and I took a lot of inspiration from her recipe, except for the canned sardines which I feel might not be necessary so I could taste how the natural ingredients do themselves.

For Laksa Utara, ROZEK TV gives me a kampong Malaysia vibe as the young Malay lady shares her recipes and the way of life there. It's a Malaysian channel also and since this laksa is from a more rural area of Malaysia, I trust her recipe is authentic.

For Laksam, another favourite channel for authentic Malaysian cooking is Che Nom. She's been doing recipe videos for a long time and also speak in Malay only so we know we're in the right place. Her videos are really aesthetic in terms of lighting and angles, so it's pleasing to watch her videos as I use her channel as the first port of call for any Malay dishes.

For Johor laksa, it's a more obscure recipe that's not commonly found since it's a high end dish. I happened to chance upon an Australian YouTuber Jackie M who partnered with a Chef Dato to demonstrate his recipe of laksa Johor. People carrying a Dato title are highly respected as the title is awarded by royalty, so again this feels like we're in the right place. I notice his Johor laksa recipe is quite similar to another laksa recipe featured in the critically acclaimed book "The Food of Singapore Malays" by Khir Johari. Khir published a recipe called "laksa Singapura" as he argues the laksa represents what is found in the region (Singapore is just next to Johor). This book is available for free in libraries so I recommend checking out this book for a rich historical analysis in Malay food.

For Indonesian food, Chef Devina is probably the most prominent creator on YouTube. She regularly appears on Indonesia TV and stars as a brand ambassador for several food and cooking brands, so her recipes should be legit Indonesian. Though her version of laksa does not use laksa leaves, the video title clearly contains the word "laksa", so it's likely her interpretation of what an Indonesian laksa should look like.

I didn't have time to get to curry mee or the Thai "laksa" which I'll explain below.

Trouble with names

While I refer to Laksa leaf throughout the video, technically it’s name is incorrect. It’s real unambiguous name is in latin, but it’s commonly called Laksa leaf in english, or daun kesum in Malay where “Daun” means leaf in Malay, while “Kesum” is a name of the leaf and doesn’t have any literal meaning. This leaf is also known as “Vietnamese Mint or Vietnamese Coriander” due to how prevalent it’s used in Vietnamese cuisine, but it is also technically incorrect as the leaf is grown across Southeast Asia and not exclusively Vietnam, and the plant is also not related to the coriander plant, according to Wiki. So I find it hard to call it either way since I want to relate to an international audience, so I hope critics would forgive me for using the term “laksa leaf” as akin to “curry leaf”. While basil leaf doesn’t have that problem because it has a clear name, people don’t call it “pesto leaf”.

I went to a Vietnamese restaurant in town, Co Chung to try out a bahn mi and I love the food photography in the menu. I ordered this bahn mi as it appears to come with laksa leaves. In the menu description, it’s just called “laksa” though. After trying just the sliver of leaf, I can confirm it is the same leaf I used in cooking my laksa and the market vendors also call it “laksa leaf”. I found the bahn mi bun too high and crispy though so I couldn’t really get a satisfying bite of all the ingredients and I had to eat the bun almost like a biscuit because it’s that crispy. But the ingredients in there have finesse as the vegetables are sliced thinly, like the cucumber, and the leaves are plucked precisely. My complaints are that the bun is not as soft as the picture looks (see those ridges that makes me think it’s soft, chewy and crispy at the same time) and the presentation is also kinda off as I don’t see the “fish cakes”. They taste like processed fish cake though as it’s rubbery and heavy in MSG so I was disappointed by the flavour and texture when it was marketed as “homemade fish cake”.

Anyway, I digressed. Another ingredient that has a troubling name is Asam Keping, which literally means “sour slices” or “sour pieces” in Malay. It is commonly known also as “tamarind slices”, and sometimes also called asam gelugor, spelled also as asam gelugo, or asam gelugur. But again, this dried peel doesn’t come from the tamarind tree we know of, and it’s actually from another tree that’s known as Asam Gelugor. “Gelugor” doesn’t really have a meaning either, but there is a town area in Penang called “Gelugor” named after the tree. The tree’s scientific name is Garcinia atroviridis and that’s unambiguous. Although it’s a useful tree cultivated widely in Malaysia for its fruit, it only has a Malay name and I guess it’s because westerners didn’t really use it that much, hence there is no english name for it. Since Asam Jawa is more widely known and accepted as “tamarind pulp”, I could call it Asam Keping without any problems. People know Asam laksa well and understand Asam means sour in Malay. But daun kesum might be a little more foreign to international friends.

Even pronunciations can vary

Even Malay words have a different pronunciation and spelling compared to the international version. Some people called out my pronunciation errors before, like oil without the L or mushy instead of mooshee. Anyway it’s because I did just pure voiceover and ambient sounds before, and now there’s a subtle background music so let’s see if I could get away with these terms. Consider “Sultan”, referring to the king of the Malay people. The British pronounce it as “sul-tan” “sulk” whereas the locals say “soo-tan” as in “soothe”.

For asam laksa, is it “asam” or “assam”? Notice the packet spells as double-s which doesn’t exist in the Malay dictionary as far as I could find.

What about the pronunciation of Kelantan and Terranganu? Locals drop the first ‘e’ and call it almost like “Klantan” or “Tranganu”. Even Sarawak becomes “Srawak”. Sometimes I get confused which is the correct pronunciation, so I guess it depends if it’s by local standards or international standards.

Where’s Turmeric?

Traditionally, turmeric is added to laksa and curries to give that distinct yellow colour. But throughout my tests of these recipes, I actually still could obtain the classic laksa colour without turmeric, so I believe it’s actually an optional ingredient given how subtle its earthy flavours are. It brings more inconvenience than flavours due to how easily it stains clothes, my countertop, and even the granite mortar and pestle. Yes, the stains can be removed and fade overtime, but I just dislike having yellow spots scattered around when the sambal is frying in oil, or when the soup splashes.

Laksa vs Curry

We’ve gone through the major laksa, but I wonder what’s the difference between laksa and curry noodles? The ingredients appear very similar, but a key differences lies in the type of leaves used.

Curry uses curry leaves from a curry tree and the leaves really have a smell comparable to curries due to its aromatic compounds that gives it a spicy, woody, citrusy, and nutty smell all at once. It’s frequently used in Asian and Indian cooking. Whereas laksa leaf is used more often in laksa as a raw topping to let its vibrant peppery flavours come through.

Compared to laksa, the curry noodles protein toppings are fairly similar too, like shredded chicken, and cockles, and tofu puffs. Veggie toppings are also bean sprouts and long beans. The base preparation is usually chicken (like chicken curry) and the standard rempah is also fried in oil till it splits, then add chicken stock to essentially form a chicken-based curry.

Where curry differs from laksa is also the use of dried spices. Curry heavily exploits the use of curry powder which is essentially turmeric, coriander, cumin, fennel, chilli, cinnamon, cloves, cardamon, which is almost every spice you can find in the grocery to mimic Indian flavors. Whereas laksa tends to be simpler like just pepper or coriander seeds to let the other flavours shine through, especially the laksa leaf.

One more key component is the souring agent. For curry, usually there’s no lime leaf or asam jawa in there because it’s supposed to be savoury instead. Whereas laksa can have abit of both to really create a multi-sensory salt fat acid and heat experience.

Is Thai Laksa a thing?

If we look further north in Thailand, we’ll find a Thai curry noodle dish called Khao Soi. It’s also a chicken-based curry but features fresh egg noodles in the curry and crispy fried noodles as a topping.

Overall, we’ll find that laksa is not really an official Thai dish, but the closest dish with similar flavours is Kanom Jeen Nam Ya. It features the unique flavours of Krachai, or finger root ginger that like ginger but with a more medicinal note to it in a good way. It also uses a typical laksa ingredients, but the way it’s served makes it distinct from laksa. Kanom Jeen serves rice noodles curled up and a fish-based coconut gravy like we’ve seen in the Laksa Utara, Laksam, and the gravy is served over rice noodles in a similar fashion as Laksa Johor, instead of immersing the noodles in a soup.

Minced laksa leaf

The laksa leaf is a surprisingly fibrous plant. Unlike spinach leaves or cabbage which soften when cooked, the laksa leaves remain tough and fibrous even after cooking for long. That's why the leaves are plucked, then rolled into a cigar and finely minced using a very sharp knife to cut the leaves up into tiny pieces, so that it could be sprinkled on the laksa to deliver that peppery flavour without the fibrousness.

If not, in one of my attempts, I added just the laksa leaves whole into the sambal tumis, and they only darken and shrink in size, but remain chewy and fibrous, even after adding in the stock, giving rise to those dark streaks which don't look so good.

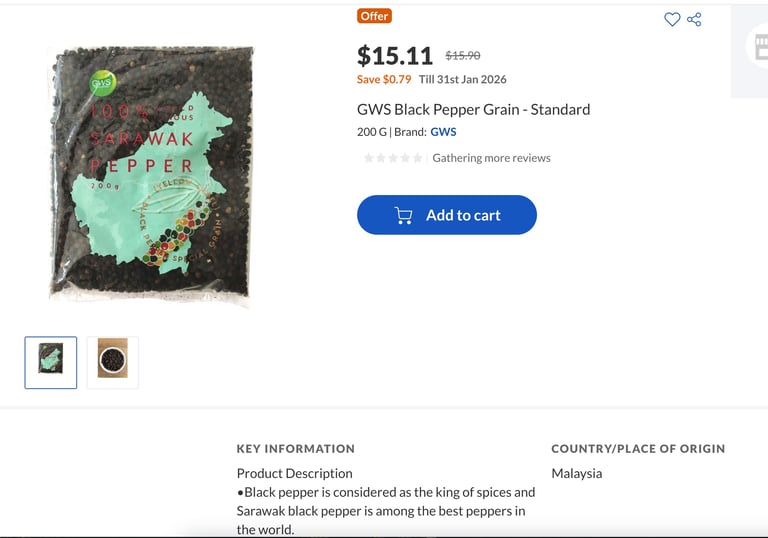

Sarawak pepper

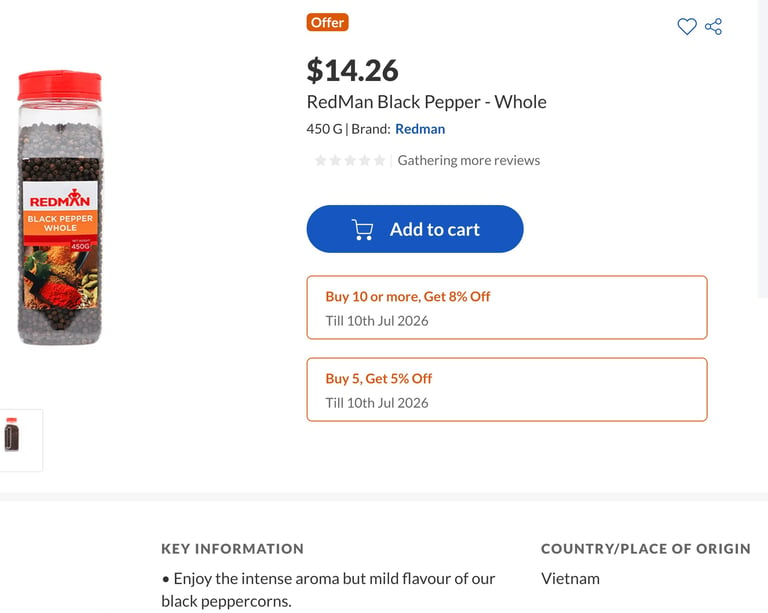

Speaking of pepper, the pepper looks pretty much the same as a normal black pepper, but it's twice as expensive.

I got this one from NTUC online (not available in stores) to ensure it's authentically from Sarawak. It costs like $60 per kg whereas a normal black pepper only goes like $28 per kg. But the Sarawak pepper is truly more aromatic and just a little bit already tastes way more peppery than the normal one which tastes light in comparison.

Strained coconut milk

When using fresh coconut milk, there will be a natural separation of brown liquid underneath while the cream floats on top. Regardless of the method used to milk the coconut, it has to be strained to remove any fibrous bits that could get in. If not, the laksa would be foamy due to the coconut fibres which have to be skimmed off to avoid the fibrous texture.

Ideal ratios of a Laksa soup base

After cooking many different kinds of laksa, I feel like I’m only barely scratching the surface of understanding what makes this dish great. We know there’s usually a rempah stir fried into a rempah, a protein stock to give that savoury liquid base, and coconut milk to enrich and thicken it. What I still don’t quite know is the ideal ratio of sambal to stock to coconut milk. There probably is some magic ratio somewhere that determines whether it ends up a nice orange hue that’s soupy, or something thick and gravy like. I think these 3 are the standard trio, before we start bringing in sour ingredients, or modifiers to the sediments nature by introducing minced fish, minced prawns etc. and there should be a golden ratio there to get the ideal sandy texture after drinking the soup, but not too much sand or clumps which happened to me a few times. Luckily I could salvage it by removing half of the material and adding more stock so it turned out fine in the end, though still a little clumpy so maybe I need to loosen it up abit more first before adding into the soup.

Admittedly, some bowls were plated with too much noodles. The intent was to show the noodles of the dish instead of submerging it in the soup. So actually the pictures have way too much noodles than what 1 person could eat. I wonder if food photographers put something in the bowl to prop up ingredients of a noodles dish. In my case, I propped it up with lots of noodles. For more inspirations behind this video, I covered them in another post behind-the-scenes.